Wagner, W. (2007). Vernacular science knowledge: its role in everyday life communication. Public Understanding of Science, 16(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662506071785

This paper argues that our understanding of how the public understands science is incomplete as long as we do not answer the question of why, under which conditions, and in which form the general public assimilate scientific background knowledge. Everyday life and communication are governed by criteria of social efficiency and evidence. Under the conditions of everyday life, it is sufficient for the lay person to possess and employ metaphoric and iconic representations of scientific facts–called “vernacular science knowledge”–that are wrong in scientific terms, as long as they are able to serve as acceptable and legitimate belief systems in discourses with other lay people. These representations are tools for a purpose that follow local rules of communication. Research within the framework of Social Representation Theory–collective symbolic coping with biotechnology in Europe, lay understanding of sexual conception, as well as traditional versus modern psychiatric knowledge in India–is presented to illustrate

Ungar, S. (2000). Knowledge, ignorance and the popular culture: climate change versus the ozone hole. Public Understanding of Science, 9(3), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/306

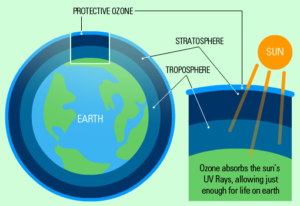

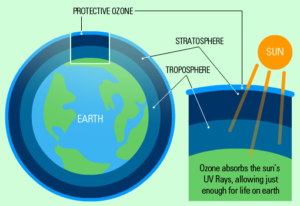

This paper begins with the “knowledge-ignorance paradox”—the process by which the growth of specialized knowledge results in a simultaneous increase in ignorance. It then outlines the roles of personal and social motivations, institutional decisions, the public culture, and technology in establishing consensual guidelines for ignorance. The upshot is a sociological model of how the “knowledge society” militates against the acquisition of scientific knowledge. Given the assumption of widespread scientific illiteracy, the paper tries to show why the ozone hole was capable of engendering some public understanding and concern, while climate change failed to do so. The ozone threat encouraged the acquisition of knowledge because it was allied and resonated with easy-to-understand bridging metaphors derived from the popular culture. It also engendered a “hot crisis.” That is, it provided a sense of immediate and concrete risk with everyday relevance. Climate change fails at both of these criteria and remains in a public limbo

Presenta: Octavio Valadez

Presenta: Octavio Valadez

Presenta: Octavio Valadez

Presenta: Octavio Valadez